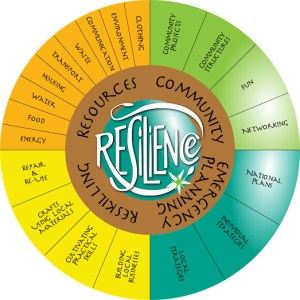

Communication underwent a radical change over a year of ‘lock down’. Face-to-face contact was very restricted, and it remains so. Fortunately, the core assumption of resilience here is that you could be physically separated from people in an adverse event of some kind.

Many people today live within a ‘community of interest’ anyway, rather than the more resilient geographical communities. This can make working from home difficult. If you couldn’t wait to put away your keyboard and chat to your neighbours, it’d be so much better. And, ultimately, considerably more resilient.

A good starting point is putting up a gate poster. In normal times, this would advertise a community event. Now, many people in our area do this to inform others about local businesses which deliver food and other essentials.

It’s even more difficult than before to meet up with your neighbours in a neutral space, so you can get to know each other. Pubs, clubs and halls have been temporarily replaced by parks. Keep this in mind when moving house, or considering a planing application for a new estate in your area. Is there a large, grassed, open space to accommodate the new reality? They’re useful for many other purposes as well, such as housing a pop-up shop or takeaway.

Deprived of human contact and retail therapy, many have turned to the internet. Local forums and Facebook pages have sprung up like edible weeds in a Resilience Garden! Make the effort to source purchases from the sites where genuine artisans can offer their wares, or buy second-hand from nearby.

Clubs and interest groups, once a great way to get to know people, have also had to adapt to the ban on face-to-face contact. Everyone is learning to use Zoom and other video chat facilities. Some are even coming to prefer these. It’s quite important that you get to know your geographical community, the people in your actual, real street, or you may end up isolated in a techno-bubble!

This probably isn’t good, and certainly isn’t resilient. Consider what idea and skills you could share with the people around you. Back to the laminated gate poster!

Dependant on the internet, what are you going to do if the mains power goes down? As explained in the Handbook, an old-fashioned plug-in landline phone doesn’t need mains power. Keep one handy; it’s worth a score of 10 in your Assessment.

It’s never been a better time to learn about radio communications. A CB radio unit can run on car batteries. It’s easy to get a foundation radio license and the course can be done on-line. In a real emergency – as opposed to a paradigm shift – Morse Code can be transmitted by very primitive equipment, and semaphore needs none at all. Learn them!

The authorities have the ability to restrict mobile phone use, and will do so in a crisis where the networks are overwhelmed. Make a plan to communicate with your family in such an emergency. For example, arrange a suitable hiding place outside where you can leave a note if you need to evacuate. Consider how much trouble people in disaster movies get into when trying to round up their family members!

You can keep your comms going much longer if you can generate your own electricity. We’re not talking about running the kettle here. One 12 volt leisure battery suitable for caravanning, fully charged, can provide several charges for a mobile phone. Learn how to use a basic solar panel system. Some are even portable enough to carry on wilderness hikes.

The role of the authorities in an emergency has become somewhat tarnished of late. Where once you needed to know how a situation was being dealt with, now you ought to know what they’re up to. The portable wind-up FM radio is still important.

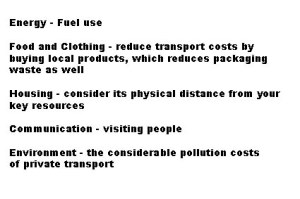

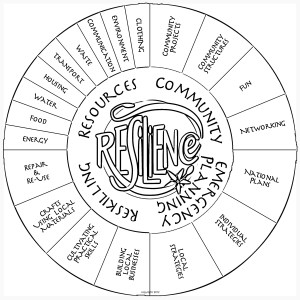

This intermittent series of posts walks you through the Resilience Assessment section by section. If you turn to the Handbook of Practical Resilience,the Communications chapter has some useful information about the energy cost of the internet, about digital compared to analogue radio signals, and the maintenance of communication lines in an emergency.

The second edition of the Handbook also contains the updated Assessment, additional instructions on how to construct a Resilience Plan, and what come next. It’s only available as a physical book. If you order from me direct, it comes with a waterproof plastic snap-top bag, ready to thrust into your grab bag! Otherwise, order it from my publishers. Or Amazon, if you really must.

Food security is covered in Recipes for Resilience. Next post I’ll describe some of the actions I took following the ‘Three Months on Stores’ project!