After my experience on the Road to Hell, I reconsidered my plan to drive to London that weekend. Clearly, more vehicles was not what the situation there needed.

I booked a ticket over the phone with Berry’s Coaches, a local firm. I boarded at Glastonbury Town Hall, read Private Eye and a newspaper, and was in Hammersmith before I had got round to the puzzles.

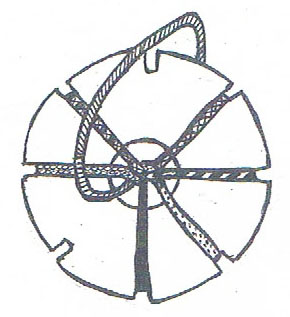

The new Underground trains were a little disconcerting. There aren’t any divisions between the carriages. You can see down the whole length of the train, how it twists and leans on the track ahead. With an Oyster card, a stranger in town has to take the fares on trust, but I’m always pleasantly surprised by its remaining balance. The entire return trip from Somerset cost me under £30.

Cheaper than the diesel for my somewhat rural camper van. No worries about overheating in traffic jams, finding somewhere to park or straying into the Low Emission Zone! I have to admit that the air quality in central London is greatly improved due to this policy, which excludes elderly diesel vans, even if it puts me to some inconvenience.

News is easy to come by here. If you’re not hooked into the direct feed of your smartphone, there are free newspapers everywhere.

I read about the London living wage campaign, to which many firms have already signed up. If workers could afford to live within walking distance of their jobs, this would reduce the commuter traffic.

Labour threatened to change the name of the House of Lords to the ‘Senate’ and move it to Manchester. This too would make a major contribution to reducing congestion. The frantic dashing of lobbyists between Houses would be offset by the regular travelling of the support staff.

Finally, such a valid reason for the HS2 that one wonders which idea has precedence here. If there’s a joined up plan, why not share it with us stakeholders who will have to pay for it?